The idea of position is key to reading Barbara Goldberg’s masterful Breaking & Entering: New and Selected Poems from The Word Works. Among the selections of new and previously published work, Goldberg uses position to show us place, placement, and power.

In “Furlough,” the opening poem, we see a father, possibly a soldier given his “tall, lean, muscular” stature, tossing his children in the air. The narrator says, “I love/ to see them drop, not weightless, but light// as grenades.” It’s chilling that “fear can be fun” and how the dad handles his kids is a kind of “hand to hand combat.” The Dresser is more than alarmed—where is the location of this poem? We know by the word dunam as in “That a dunam// of earth is worth dying for?” Only in Israel is land measured in this way—a dunam is equal to one thousand square meters. And thereby we understand that this man is on temporary hiatus (furlough) from his military duties and is now attending to his family responsibilities.

In Goldberg’s first book Berta Broadfoot and Pepin the Short: A Merovingian Romance, a working-class girl Aliste replaces Berta, a king’s royal bride. Aliste’s mother Margiste, a “trusted handmaiden to Queen Blancheflor,” Berta’s mother, has been entrusted to deliver Berta to her bridegroom. Except Margiste wants more for her daughter who is also Berta’s half-sister. In “Aliste Considers Her Position,” placement is seriously contemplated, but Aliste feels powerless.

Who was there to turn to when I found

his morning gift, a handsome brooch

encrusted with pearls, on my pillow?

…

Not Mother, hopping about with glee, fingers

greasy from palace meat. She pokes my ribs

and cackles, “We fooled him, eh? We two

make quite a team.”

… while I,

dumb sheep, play the part of Queen.

… I’ve thought of claiming

defect of consent, diriment impediment, but

Mother would be lost for good, poor sheep.

In subsequent books by Goldberg—Cautionary Tales, Marvelous Pursuits, The Royal Baker’s Daughter, and Kingdom of Speculation—the pursuit of power looms large with an ample

dash of deception.

Consider in “The Future Has Already Happened” (from Cautionary Tales) how a little girl known as Red Riding Hood has not only triumphed over the wolf but sees this as the future with the woodcutter for her own progeny.

…Imagine the wild Caesarean,

the ax and its fresh cut, the blade

running deep. And me springing out

to dance on the planked floor with Granny

…

Give serious attention to “Ballad of the Id” (from Marvelous Pursuits) an internal powerhouse that seems inescapable.

I am your rose hips and bunting and bootleg

and I am your black bangs those devil’s

spikes

… without me you’re puny and

pallid and prudish …

I bit your sister and squealed on the porter

and who pulled you out of the muck of intention

…who stole your tom-tom

just ask and I’ll tell you I did I did

Evaluate Goldberg’s duplicity carefully when you read “Fairytale” (from The Royal Baker’s Daughter).

Once upon a time

a baby boy was born

to a suicidal woman

and a suicidal man.

He was not born to make her sane

nor to help the marriage last

but because his birth would save

his daddy from the draft.

…

The little boy is now a man

and takes himself a wife.

One hand gently strokes her hair,

the other strokes his knife.

The knife represents power, but might the knife be a stand-in for his penis? Certainly, sex can be another tool of power.

The final set of selections from Kingdom of Speculation take romances, fairytales, cautionary tales, and psychological treatises to a heightened level of power. Could these poems be stories of Balkis—Queen of Sheba or the woman Hatshepsut who became the Pharaoh Hatshepsu (a woman pharoah who presented herself as a man)? In “The Master of Chance,” we meet “The Princess looking no more/ like a Princess than you or I” who dwells in “the Province of Chance.” It’s an odd exchange between a shabby royal and a card-playing man calling himself the Master of Chance. He wants her to marry him so she can polish his casket of gold which she recognizes as one that had belonged to her father. The poem ends with the man asserting his power:

A woman in my employ, as is everyone

in this State, for I’m the Master

of Chance, I cut the deck, declare

what’s wild, as you are my dear, my Balkis,

my Hatshepsut, my true Queen of Hearts.

“A Great Darkness Falls,“ the last poem of Breaking & Entering we recognize the shabby princess who now has possession of the King’s coffer which she uses as “a fertile bed/ for her cuttings and seeds” while incubating in her purse the “Egg of perfection.”

… All is poised for

an ever after. Sing praise to the Great

Lord Chaos, his enabling dark. Praise

to the touch of a choice companion.

And praise to the Egg of Perfection

glowing in the folds of a lady’s purse.

These lines

close the book on all Goldberg’s books in that wish for a fairytale ending that

provides love, union, and progeny, while placing the power in the female grip.

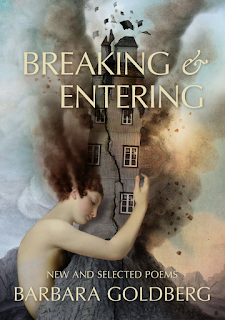

The book’s title Breaking & Entering comes from the poem “Alarums and Excursions” (from Marvelous Pursuits). The poem deals with a modern-day woman who interacts with a security professional, “a man who knows the tricks of breaking/ and entering and how to secure all she holds/ dear from those who would trespass against her.” The cover image, a digital artwork entitled “Tower” by Catrin Welz-Stein shows a youthful nude maiden (a figure like those in Renaissance paintings by Titian) embracing the bottom of a tall building built possibly on a volcano and which is breaking apart and on fire. The nude’s long hair is swept up in the wind of the explosion. The image speaks ably to the explosive emotional content of Goldberg’s book which presciently summons our current day turmoil that deals with place, placement, and power as well as truth and lies.